Students on Strike

Compiled from archive issues of the University of Omaha’s Gateway student newspaper and “A History of the University of Nebraska at Omaha: 1908-1983.”

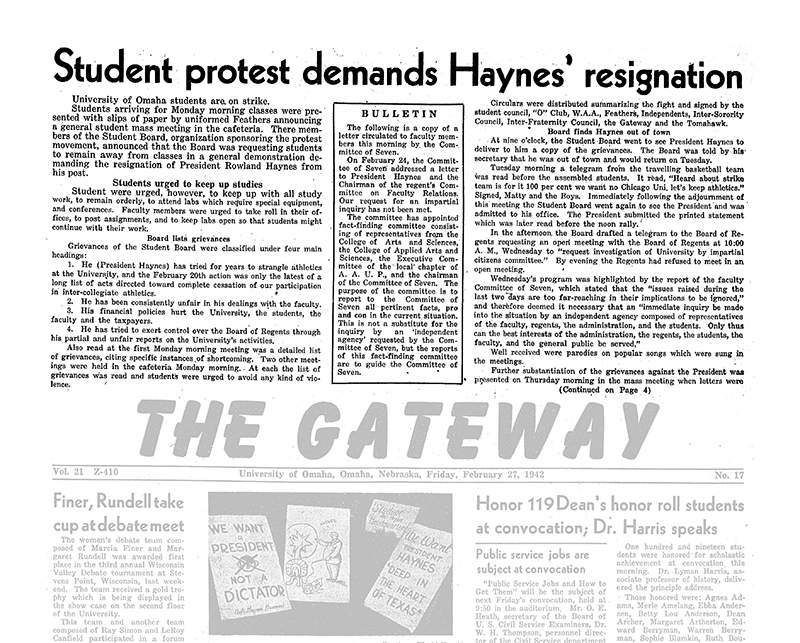

The lead story in the Gateway began with a bang: “University of Omaha students are on strike.”

A protest from the radical ’60s, perhaps? Maybe the ’70s?

Nope. The strike came in February 1942 when OU students skipped class for a week while demanding the resignation of then-President Rowland Haynes.

OU students showed for class on Monday, Feb. 24, of that year and were asked to attend a general student mass meeting in the cafeteria. There, the Student Board listed four grievances against Haynes:

1. He (President Haynes) has tried for years to strangle athletics at the University, and the February 20th action was only the latest of a long list of acts directed toward complete cessation of our participation in inter-collegiate athletics.

2. He has been consistently unfair in his dealings with the faculty.

3. His financial policies hurt the University, the students, the faculty and the taxpayers.

4. He has tried to exert control over the Board of Regents through his partial and unfair reports on the University’s activities.

The grievances were read at two other cafeteria meetings that Monday. Students “were urged to avoid any kind of violence,” and to “keep up with all study work, to remain orderly, to attend labs which require special equipment, and conferences.” A request was made that an independent agency make an impartial inquiry into the situation.

Regarding Haynes and athletics, notes UNO History Professor Tommy Thompson in his book, “A History of the University of Nebraska at Omaha,” students disliked that Haynes had not signed contracts with North Central Conference teams for football and basketball games as of the 1942-1943 school year. Haynes said the exodus of male students to fight in World War II had left OU with too few athletes and a reduced tuition income that affected support of athletics.

Regarding Haynes and athletics, notes UNO History Professor Tommy Thompson in his book, “A History of the University of Nebraska at Omaha,” students disliked that Haynes had not signed contracts with North Central Conference teams for football and basketball games as of the 1942-1943 school year. Haynes said the exodus of male students to fight in World War II had left OU with too few athletes and a reduced tuition income that affected support of athletics.

“Students, though, felt Haynes was using the war as an excuse to destroy intercollegiate athletics at the Municipal University,” Thompson wrote. “After all, he had praised the University of Chicago for ending football just a few years earlier.”

As for Haynes’ relationship with faculty, Thompson notes students’ disappointment with their president’s refusal to adopt a tenure system.

Students presented a copy of their grievances to Haynes but were told he was out of town. So was the basketball team, which sent a telegram to their fellow students reading, “Heard about strike team is for it 100 per cent we want no Chicago Uni. Let’s keep athletics.”

A faculty-led Committee of Seven on Wednesday of that week felt the “issues raised during the last two days are too far-reaching in their implications to be ignored,” and also requested an “immediate inquiry be made into the situation by an independent agency composed of representatives of the faculty, regents, the administration, and the students.

Students continued to meet. “Well received were parodies on popular songs which were sung in the meetings,” noted the Gateway.

One week later, students were back in their classes. The Committee of Seven had formed a four-member fact-finding body and the Board of Regents sanctioned a board of inquiry to study the grievances.

The Gateway reported that Regents President Dale Clark “thought it strange, at the first committee meeting Tuesday, that ‘a continuity of unrest against Haynes appears back several years although student bodies change from year to year.’”

The Board of Inquiry, Thompson writes, “decided that several of the students’ complaints were not substantiated by the evidence, but that some of the issues needed corrective action. The Regents decided intercollegiate athletics could continue for another year if more flexible arrangements could be made with the North Central Conference teams. The conference did agree that games could be cancelled if a school had insufficient funds or players. For faculty, in 1942 and 1943, the Regents adopted a tenure system by which a faculty member could receive tenure after a stated period of service.”

Haynes, hired in 1935, remained as president and would stay in that post until retiring in 1948.

Haynes proved correct, Thompson later adds, on the question of athletics. “There was now no real protest from students when the University ended football for the duration of the war and did likewise for basketball after a team played a schedule of primarily state teams in the spring of 1944. Naturally many activities of the University in addition to athletics felt the loss of those individuals who left the school due to World War II. In all, almost thirteen hundred and fifty students and faculty, men and women, served in the military.”